Table of content

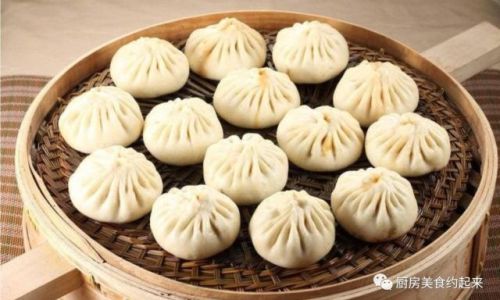

Steaming buns, a cornerstone of Asian cuisine, particularly in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean traditions, is both an art and a science. The debate over whether to use cold water or hot water when steaming buns has persisted among home cooks and culinary experts alike. This article delves into the chemistry, physics, and culinary techniques behind steaming buns to answer this question definitively. By exploring the role of temperature, dough composition, and steam dynamics, we will uncover the optimal method for achieving light, fluffy, and perfectly textured buns every time.

The Basics of Steaming Buns

Steaming is a cooking method that uses vaporized water to transfer heat to food. Unlike baking or frying, which rely on direct heat, steaming preserves moisture, nutrients, and delicate flavors. For buns, this method is ideal because it creates a tender crumb and a soft, velvety exterior. The key to successful steaming lies in controlling temperature and humidity to ensure even cooking and proper dough expansion.

Buns are typically made from a simple dough of flour, water, yeast (or leavening agents), and sometimes sugar or fat. The yeast ferments sugars, producing carbon dioxide gas that inflates the dough, creating air pockets. During steaming, the heat kills the yeast, halting fermentation, and the steam’s heat and moisture gelatinize the starches in the flour, solidifying the bun’s structure.

The Cold Water vs. Hot Water Debate

The controversy revolves around whether to start steaming with cold water (allowing the water to heat gradually) or hot water (preheating the steamer before adding the buns). Each approach has advocates, but understanding the underlying principles reveals which method yields superior results.

The Case for Cold Water Steaming

Gradual Temperature Rise: Starting with cold water allows the steamer to heat slowly. This gradual temperature increase mirrors the proofing process, where dough rises in a warm environment. As the water heats, the steam generated is less intense initially, giving the buns time to expand uniformly. The slow rise in temperature prevents the dough from shocking, which can occur when exposed to sudden high heat, potentially causing the buns to collapse or develop a dense texture.

Yeast Activation: Yeast remains active until temperatures reach around 140°F (60°C). When using cold water, the yeast continues to ferment as the water warms, producing additional gas and enhancing the bun’s rise. This extended fermentation period contributes to a more complex flavor profile, as the yeast generates subtle alcoholic and aromatic compounds.

Even Cooking: Cold water steaming ensures that the heat penetrates the buns from all sides simultaneously. The gradual increase in temperature reduces the risk of overcooking the exterior while the interior remains underdone. This method is particularly forgiving for novice cooks, as it minimizes the margin for error.

Texture and Appearance: Buns steamed with cold water tend to have a smoother, shinier surface due to the controlled condensation of steam. The slow release of moisture prevents the dough from becoming overly saturated, which can lead to a gummy or sticky texture.

The Case for Hot Water Steaming

Time Efficiency: Preheating the steamer with hot water reduces cooking time. The high initial temperature jump-starts the cooking process, which is advantageous in commercial kitchens or when preparing large batches. However, this method requires precise timing to avoid overcooking.

Immediate Lift: Hot water steaming can create a sudden burst of steam, which some bakers believe gives the buns an initial “lift.” This might be beneficial for recipes using chemical leaveners like baking powder, which activate quickly at high temperatures. However, for yeast-leavened buns, this rapid heat can compromise the structure.

Crispier Exterior (in Some Cases): While buns are typically soft, certain variations (e.g., shengjianbao, pan-fried buns) benefit from a crispier base. Hot water steaming, combined with a preheated pan, can achieve this texture. However, this is an exception rather than the rule for traditional steamed buns.

The Science of Steam and Dough Interaction

To understand why cold water steaming is often superior, we must examine the interplay between heat, moisture, and dough chemistry.

Gelatinization of Starches

Flour contains starches that absorb water and swell when heated, a process called gelatinization. This process begins around 140°F (60°C) and peaks at 180°F (82°C). Cold water steaming ensures that starches gelatinize gradually, creating a uniform, cohesive matrix. Rapid heating from hot water can cause uneven gelatinization, leading to a grainy or dense texture.

Protein Coagulation

Gluten, the protein network in flour, coagulates (denatures) at 158°F (70°C). Proper coagulation is critical for structure; undercooked gluten results in a gummy bun, while overcooked gluten becomes tough. Cold water steaming allows gluten to coagulate steadily, balancing tenderness and elasticity.

Moisture Retention

Steam is 100% humid, so the bun’s surface remains moist during cooking. However, excessive moisture can dissolve surface starches, creating a sticky layer. Cold water steaming regulates moisture absorption by introducing humidity gradually, preventing sogginess.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Overcrowding the Steamer: Buns need space to expand. Overcrowding traps steam, causing uneven cooking and wrinkled surfaces.

- Opening the Lid Too Soon: Releasing steam before cooking is complete causes temperature drops, which can deflate buns.

- Ignoring Dough Hydration: Too much water makes dough sticky; too little results in dry buns. Aim for 50–60% hydration (by flour weight).

- Using Old Yeast: Dead yeast won’t ferment, leading to dense buns. Always proof yeast in warm water before mixing.

Tips for Perfect Steamed Buns

- Proof Dough Properly: Let dough rise until doubled in size. Underproofed buns are dense; overproofed buns collapse.

- Line the Steamer: Use parchment or cabbage leaves to prevent sticking.

- Control Steam Flow: Maintain a consistent, gentle stream of steam. Avoid vigorous boiling, which creates uneven bubbles.

- Rest After Steaming: Turn off the heat and let buns sit for 5 minutes before removing the lid. This prevents sudden temperature changes.

Cultural and Historical Context

Steaming has been a cooking method in China for over 4,000 years, with early steamer baskets made from bamboo or clay. Traditional recipes, like mantou (plain steamed buns) and baozi (filled buns), emphasize simplicity and respect for ingredients. The cold water method aligns with these traditions, as it mirrors the patience and precision required to master steaming.

In modern times, electric steamers and instant pots have simplified the process, but the core principles remain unchanged. Whether using a rustic bamboo steamer or a sleek appliance, the goal is to harmonize heat, moisture, and dough.

Conclusion: The Verdict on Cold Water Steaming

After examining the evidence, cold water steaming emerges as the superior method for most bun recipes. Its gradual temperature rise supports yeast activity, even cooking, and optimal texture development. While hot water steaming has niche applications, it risks compromising the bun’s structure and flavor.

For home cooks seeking foolproof results, cold water steaming is the gold standard. It requires minimal equipment, accommodates varying skill levels, and delivers consistently delicious buns. So, the next time you crave a warm, fluffy bun, fill your steamer with cold water and let science work its magic. Your taste buds—and your Instagram followers—will thank you.

0 comments