Table of content

Zongzi, a traditional Chinese rice dumpling wrapped in bamboo or reed leaves, holds a cherished place in culinary history, particularly during the Dragon Boat Festival. These pyramid-shaped treats, filled with ingredients like glutinous rice, red bean paste, pork, or salted egg yolk, require precise cooking methods to achieve their signature sticky texture and harmonious flavors. A common dilemma for home cooks and food enthusiasts alike is whether to boil frozen zongzi in cold water or drop them directly into boiling water. This article delves into the scientific principles, cultural practices, and practical tips surrounding this question, offering a comprehensive guide to perfecting this ancient dish.

The Cultural Significance of Zongzi

Before addressing the cooking technique, it is essential to appreciate the cultural weight of zongzi. Dating back over 2,000 years, zongzi commemorates the legendary poet Qu Yuan, who drowned himself in the Miluo River to protest corruption. Locals threw rice dumplings into the river to prevent fish from devouring his body, a ritual that evolved into the Dragon Boat Festival’s central tradition. Today, zongzi symbolizes unity, respect for heritage, and the art of balancing flavors—a metaphor for life’s complexities.

The Frozen Zongzi Conundrum

Modern lifestyles have transformed zongzi from a seasonal, homemade delicacy into a convenience food available year-round. Freezing zongzi preserves their shelf life but introduces a new challenge: how to reheat them without compromising texture or taste. The debate over water temperature hinges on two factors: thermal shock and even cooking.

Thermal Shock: The Enemy of Texture

Glutinous rice, the primary ingredient, behaves unpredictably when exposed to rapid temperature changes. Placing frozen zongzi into boiling water subjects the outer leaves and rice to abrupt heating, causing the leaves to contract sharply. This thermal shock can tear the bamboo or reed wrappers, releasing sticky rice grains into the water and resulting in a mushy, broken exterior. Conversely, starting with cold water allows gradual thawing and heating, preserving the dumpling’s structural integrity.

Even Cooking: The Key to Flavor

Zongzi’s filling—whether savory (e.g., pork belly with mushrooms) or sweet (e.g., lotus seed paste)—requires uniform heating to meld flavors. Boiling in cold water ensures that heat penetrates from the outside in, allowing the rice to absorb moisture evenly and the filling to reach the ideal temperature without overcooking. Direct boiling can create a gradient where the exterior becomes waterlogged while the interior remains frozen, leading to uneven texture and compromised taste.

The Scientific Rationale for Cold Water Boiling

To understand why cold water is preferable, one must examine the physics of heat transfer. When submerged in cold water, the zongzi’s temperature rises incrementally. This slow process allows the rice’s starch molecules to gelatinize uniformly, creating a cohesive, chewy texture. Additionally, the gradual increase in water temperature prevents the leaves from separating prematurely, sealing in aromas and flavors.

Starch Gelatinization: A Delicate Balance

Glutinous rice contains approximately 75–80% amylopectin, a starch molecule that contributes to its sticky texture when cooked. Gelatinization—the process where starch granules absorb water and swell—occurs between 60°C (140°F) and 85°C (185°F). Starting in cold water ensures that gelatinization happens progressively, preventing the rice from becoming either undercooked (grainy) or overcooked (gummy).

Leaf Integrity and Aroma Retention

Bamboo or reed leaves impart a subtle grassy aroma to zongzi. Rapid boiling can cause the leaves to release volatile compounds too quickly, resulting in a bitter aftertaste. Cold water boiling allows the leaves to release their essence gradually, infusing the rice with a delicate fragrance.

Step-by-Step Guide to Boiling Frozen Zongzi

- Preparation: Remove zongzi from the freezer and unwrap any plastic packaging. Do not thaw them at room temperature, as this can promote bacterial growth.

- Select the Right Pot: Use a large pot with a lid to accommodate the zongzi without overcrowding. A depth of at least 15 cm (6 inches) ensures even submersion.

- Cold Water Immersion: Place the frozen zongzi in the pot and cover with cold water. The water level should exceed the zongzi by 5 cm (2 inches) to prevent uneven cooking.

- Add Flavor Enhancers (Optional): A pinch of salt, a bay leaf, or a strip of dried tangerine peel can elevate the broth’s flavor without overpowering the zongzi.

- Gradual Heating: Bring the water to a gentle simmer over medium heat. Avoid rapid boiling, which can jostle the zongzi and damage the leaves.

- Cooking Time: Boil for 25–35 minutes, depending on the zongzi’s size. Larger varieties (e.g., those stuffed with whole duck eggs) may require 40 minutes.

- Resting Period: Once cooked, remove the pot from heat and let the zongzi sit in the water for 5–10 minutes. This allows residual heat to finish cooking and firms up the texture.

Alternative Cooking Methods: Steaming vs. Pressure Cooking

While boiling is traditional, steaming and pressure cooking offer viable alternatives for those seeking speed or texture variations.

Steaming

Steaming frozen zongzi preserves their shape exceptionally well, as the moist heat circulates without direct water contact. Place a steamer basket in a pot, add water, and bring to a boil. Arrange the zongzi in a single layer, cover, and steam for 20–30 minutes. This method is ideal for sweet zongzi, as it prevents sugar from leaching into the water.

Pressure Cooking

A pressure cooker reduces cooking time by 50%, making it suitable for busy households. Add 500 ml (2 cups) of water and a trivet to the cooker, place the zongzi on top, and cook at high pressure for 12–15 minutes. Release pressure naturally to avoid thermal shock.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Using Hot Water: As discussed, this risks leaf tears and uneven cooking.

- Overcrowding the Pot: Crowded zongzi may stick together, trapping steam and causing sogginess.

- Skipping the Resting Period: Removing zongzi immediately from heat can lead to a gummy center.

- Reheating in a Microwave: While convenient, microwaves heat unevenly, often drying out the rice or bursting the leaves.

The Role of Fillings in Cooking Time

The density and moisture content of fillings influence cooking duration. For example:

- Pork-filled zongzi: Require longer cooking to render fat and tenderize meat.

- Red bean paste zongzi: Cook faster due to the absence of protein.

- Vegetarian zongzi: May need slightly less time to avoid over-soaking the rice.

Adjust cooking time by 5–10 minutes based on the filling’s composition.

Storage and Freezing Best Practices

To ensure optimal results when reheating, proper freezing is critical:

- Cool Completely: After cooking, let zongzi cool to room temperature before freezing.

- Wrap Tightly: Use airtight plastic wrap or freezer bags to prevent freezer burn.

- Label and Date: Frozen zongzi last 3–6 months when stored at -18°C (0°F).

Cultural Nuances: Regional Variations in Zongzi

China’s vast culinary landscape has spawned countless zongzi variations, each with unique cooking traditions:

- Southern China (Guangdong): Alkaline-treated rice gives zongzi a golden hue; boiled in water flavored with dried tangerine peel.

- Northern China (Beijing): Sweet zongzi with jujube or red bean paste are often steamed.

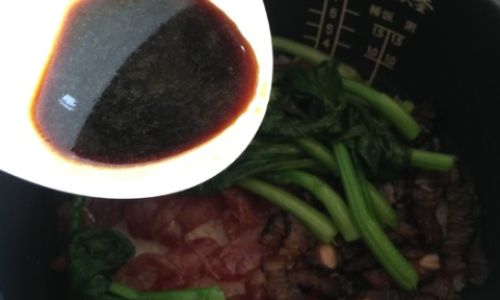

- Zhejiang Province: Savory zongzi with pork belly and chestnuts are slow-boiled in a mixture of soy sauce and rice wine.

Adhering to regional cooking methods can enhance authenticity, though the cold water boiling principle remains universal.

Modern Adaptations: Health-Conscious and Vegan Zongzi

Contemporary cooks are experimenting with low-fat fillings, gluten-free rice, and alternative leaves (e.g., corn husks). These innovations require slight adjustments to cooking times and water ratios. For instance, quinoa-based zongzi may need less water to avoid sogginess, while vegan varieties with mushrooms and tofu benefit from longer simmering to develop umami flavors.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Soggy Rice | Overboiling or insufficient draining | Reduce cooking time by 5 minutes; drain immediately after cooking. |

| Dry Rice | Undercooking or high heat | Increase cooking time; use a lid to trap steam. |

| Burst Leaves | Rapid temperature changes | Use cold water boiling; avoid stirring vigorously. |

| Unevenly Cooked Filling | Insufficient simmering time | Extend cooking by 10 minutes; consider pressure cooking. |

The Aesthetic and Sensory Experience

Beyond technicalities, zongzi appreciation is a multisensory experience. The act of unwrapping the leaf, inhaling the aromatic steam, and savoring the contrast between sticky rice and savory or sweet filling is integral to its allure. Cold water boiling enhances this ritual by ensuring the zongzi emerges intact, visually appealing, and true to its cultural essence.

Conclusion: Honoring Tradition Through Technique

The question of whether to boil frozen zongzi in cold water is more than a culinary query—it is a gateway to understanding the intersection of science, tradition, and sensory pleasure. By embracing the cold water method, cooks honor the meticulous craftsmanship of generations past while ensuring that each bite of zongzi delivers the perfect balance of texture, flavor, and nostalgia. Whether enjoyed during the Dragon Boat Festival or as a year-round treat, properly cooked zongzi remains a testament to the enduring power of culinary heritage.

0 comments