Introduction

Bòbōjī, a beloved dish from China’s Sichuan province, has sparked culinary curiosity worldwide. At its core, it consists of skewered meats, vegetables, and offal marinated in a vibrant, numbing-spicy sauce. Yet, beneath its fiery surface lies a question that divides food enthusiasts: Should Bòbōjī be served cold, as tradition dictates, or hot, as some modern adaptations suggest? This article explores the history, cultural context, and contemporary interpretations of this iconic dish to unravel the mystery behind its ideal serving temperature.

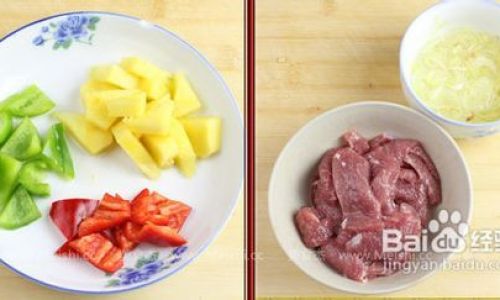

Historical Roots and Traditional Preparation

To understand the temperature debate, one must first trace Bòbōjī’s origins. The dish hails from Leshan, a city in Sichuan, where it emerged as a street food staple. The name “Bòbōjī” refers to the clay pots (bòbō) used to serve the dish, which were traditionally filled with a cold broth. Historically, vendors would prepare the skewers in advance, marinating them in a mixture of chili oil, Sichuan pepper, garlic, and spices, then chill them before selling. This method aligned with Sichuan’s climate—hot and humid—making cold dishes refreshing and practical for outdoor consumption.

The cold preparation also served a functional purpose. By marinating ingredients in a flavorful broth and serving them chilled, vendors could preserve the dish for hours without refrigeration, relying on salt, vinegar, and spices to inhibit bacterial growth. This approach ensured that Bòbōjī remained safe to eat in Leshan’s sweltering summers.

The Case for Cold Bòbōjī: Tradition and Texture

Advocates for cold Bòbōjī argue that temperature is integral to its identity. The dish’s signature “numbing-spicy” flavor (málà), derived from Sichuan pepper and chili, is intensified when served cold. The chill numbs the palate slightly, creating a contrast with the fiery spices that enthusiasts describe as addictive. Moreover, the cold broth allows the ingredients’ textures to shine—crisp vegetables, tender meats, and chewy offal retain their individuality without becoming mushy from heat.

Traditional recipes reinforce this perspective. Authentic Bòbōjī broth is made by simmering chicken or pork bones with aromatics, then cooling the liquid to room temperature before adding skewers. The absence of heat ensures the broth’s flavors meld subtly over time, creating a harmonious balance. Purists insist that deviating from this method compromises the dish’s essence.

The Rise of Hot Bòbōjī: Innovation and Regional Variations

Despite its cold origins, hot Bòbōjī has gained traction in recent years. This adaptation often surfaces in restaurants outside Sichuan, where chefs experiment with serving the dish warmed to enhance comfort during colder months. Proponents argue that heat opens the pores of the ingredients, allowing the broth to penetrate deeper and amplify flavors. Some variations even incorporate simmering the skewers in the broth before serving, creating a hybrid between Bòbōjī and hot pot.

Regional preferences play a role too. In northern China, where winters are harsh, hot dishes are more common. Some vendors in Beijing or Shanghai now offer heated Bòbōjī, catering to local tastes. Similarly, international adaptations—such as in the U.S. or Europe—often default to hot preparations, assuming diners expect warmth from Chinese street food.

The Sauce Conundrum: Does Temperature Alter Flavor?

Central to the debate is the sauce itself. Bòbōjī’s broth is a complex blend of chili oil, fermented soybean paste, garlic, vinegar, and Sichuan pepper. Cold broth allows the numbing sensation of Sichuan pepper to linger, creating a tingly aftertaste. Heat, however, mellows this effect, softening the pepper’s intensity while releasing the chili oil’s fragrance.

Chefs who prefer cold Bòbōjī argue that the chill preserves the sauce’s layers, letting each component—sweet, sour, spicy, and umami—shine individually. Those in favor of heat counter that warmth integrates these flavors, creating a cohesive taste profile. This divergence reflects broader culinary philosophies: some prioritize texture and temperature contrasts, while others seek unified flavor experiences.

Cultural and Practical Considerations

The temperature debate also intersects with cultural symbolism. In Sichuan, cold dishes like liángcài (cold appetizers) are revered for their simplicity and connection to nature. Bòbōjī’s cold preparation aligns with this tradition, embodying the region’s philosophy of harmonizing food with climate. Conversely, hot dishes symbolize warmth and communal dining, values emphasized in northern Chinese cuisine.

Practicality further complicates the issue. Street vendors in Leshan rely on cold Bòbōjī for its portability and longevity. Heat would require constant fire sources, complicating logistics. However, modern kitchens with advanced equipment can maintain hot broths without hassle, enabling creative freedom.

Expert Opinions: Chefs and Historians Weigh In

Culinary historians note that historical texts rarely specify Bòbōjī’s temperature, leaving room for interpretation. “The earliest recipes describe a ‘chilled broth,’ but language barriers and regional dialects might have led to misunderstandings,” explains Dr. Li Wei, a food scholar at Sichuan University. He adds, “The dish’s adaptability is its strength—it’s evolved over centuries, and temperature is just one facet of that.”

Chefs, too, are divided. “Tradition matters,” says Master Chef Zhang Hua of Chengdu’s century-old Chen Mapo Tofu Restaurant. “Changing the temperature is like rewriting history.” Yet, young chef Liu Yan of Beijing’s Hot & Cold Kitchen disagrees: “Innovation keeps cuisine alive. My hot Bòbōjī with black truffle is a bestseller—customers love the contrast.”

Global Adaptations: Fusion Without Borders

Outside China, Bòbōjī’s temperature debate takes on new dimensions. In the U.S., where Chinese-American cuisine often blends traditions, chefs like Danielle Chang of Lucky Rice Festival serve both versions. “It’s about education,” she says. “We explain the origins but let diners choose.” Similarly, in London, Baozi Inn offers a “build-your-own” Bòbōjī bar with heated broth options, appealing to adventurous foodies.

These adaptations highlight the dish’s versatility. While purists may scoff, global audiences embrace the flexibility, proving that culinary traditions can thrive through evolution.

Health and Taste Preferences: A Personal Choice

Beyond tradition and innovation, health and taste preferences influence temperature choices. Cold Bòbōjī is often perceived as lighter, suitable for appetizers or summer meals. The chill can also soothe spice-induced heat, making it approachable for less adventurous eaters. Hot Bòbōjī, on the other hand, is comforting, ideal for colder climates or main courses. Its warmth may aid digestion, a belief rooted in traditional Chinese medicine.

Ultimately, the decision hinges on individual palates. Some savor the cold’s crispness, while others crave the heat’s embrace.

Conclusion: Embracing the Spectrum

The debate over Bòbōjī’s temperature reflects a broader truth: culinary traditions are not static. While cold Bòbōjī honors its Sichuanese roots, hot adaptations demonstrate the dish’s adaptability. Both versions coexist, offering diners choices without diminishing the other’s validity.

In Leshan, vendors still serve the dish cold, preserving a centuries-old ritual. Across oceans, chefs experiment with heat, inviting new audiences to savor its magic. Perhaps the answer lies not in choosing sides, but in appreciating the spectrum—a testament to Bòbōjī’s enduring appeal. Whether hot or cold, one thing is certain: this humble skewered dish will continue to spark passion, one fiery bite at a time.

0 comments