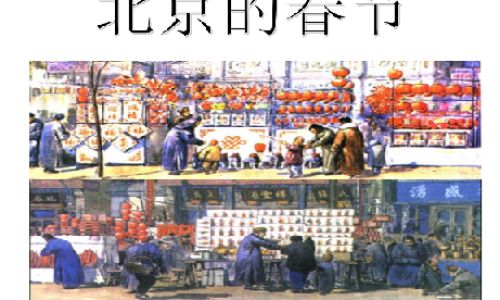

The Spring Festival, or Chinese New Year, is the most cherished and elaborate holiday in Beijing, a city where ancient traditions blend seamlessly with modernity. For Beijingers, this festive season is not merely a celebration but a culinary odyssey—a time when families gather to honor their heritage through meticulously prepared dishes that carry centuries of symbolic meaning. The foods consumed during this period are not just sustenance; they are vessels of hope, prosperity, and togetherness. This article explores the intricate tapestry of Beijing’s Spring Festival cuisine, delving into the specific dishes, their cultural significance, and the rituals that accompany their preparation and consumption.

New Year’s Eve: The Pinnacle of Culinary Celebration

The climax of Beijing’s Spring Festival festivities occurs on New Year’s Eve, a night when kitchens transform into bustling hubs of activity. The centerpiece of this meal is undeniably jiǎozi (dumplings), a dish so integral to the holiday that it is often referred to as the “currency of reunion.” Families gather hours before midnight to craft these crescent-shaped delights, a practice that fosters intergenerational bonding. The dumplings’ shape mirrors ancient Chinese gold ingots, symbolizing wealth and prosperity. Many households tuck a coin, a peanut, or a candy into one dumpling—whoever bites into it is believed to receive good fortune in the coming year.

But Beijing’s New Year’s Eve spread extends far beyond dumplings. Nián gāo (sticky rice cake) is another staple, its glutinous texture embodying the hope for a “sweeter” and more cohesive family life. Steamed or fried, this dish is often sweetened with red bean paste or brown sugar, with the color red symbolizing joy and luck. In some homes, nián gāo is sliced and stir-fried with vegetables or meat, creating a savory-sweet balance that mirrors the holiday’s dual themes of indulgence and moderation.

No Beijing New Year’s Eve table is complete without a whole fish—typically carp or mandarin fish. The Chinese word for fish, yú, sounds like the word for “surplus,” making this dish a powerful emblem of abundance. The fish is steamed to perfection, drizzled with soy sauce, and garnished with ginger and cilantro. Crucially, it is served whole, with head and tail intact, to signify a prosperous beginning and end to the year. Leftovers are deliberately preserved, as the phrase nián nián yǒu yú (“may there be surpluses every year”) reinforces the desire for ongoing prosperity.

Reunion Dinner: A Symphony of Flavors and Symbolism

The reunion dinner on New Year’s Day is a lavish affair, featuring dishes that cater to both the palate and the soul. Sì jì dòu cài (four-season vegetable stir-fry) is a colorful medley of fresh, seasonal ingredients like bamboo shoots, mushrooms, and snow peas. Each vegetable represents a season, symbolizing harmony with nature’s cycles. The dish’s vibrant hues also align with the festive aesthetic, with red peppers and green beans adding visual flair.

Another highlight is chūn juǎn (spring rolls), golden-brown pastries filled with a mixture of shredded vegetables and meat. Their cylindrical shape and crispy texture evoke images of gold bars, making them a popular choice for attracting wealth. Families often prepare spring rolls together, with children delighting in the tactile process of wrapping the fillings.

For those seeking a heartier option, hóng shāo ròu (braised pork belly) is a crowd-pleaser. The meat is slow-cooked in soy sauce, sugar, and spices until it achieves a melt-in-the-mouth tenderness. The dish’s rich, caramelized glaze represents the desire for a life as fulfilling as its flavor. Paired with steamed buns or rice, it is a testament to Beijing’s culinary artistry.

Sweet Endings and Auspicious Snacks

No Beijing Spring Festival meal is complete without desserts that satisfy the sweet tooth while invoking blessings. Táng guǒ (candied fruits and nuts) are a common treat, with varieties like hawthorn balls, lotus root slices, and walnuts coated in sugar syrup. These confections are often arranged in decorative bowls, their vibrant colors and glossy finishes adding to the festive decor.

Bā bǎo fàn (eight-treasure rice pudding) is another showstopper. Made with glutinous rice, red bean paste, and an assortment of dried fruits and nuts, this dessert is steamed until the ingredients meld into a sticky, fragrant mass. The “eight treasures” symbolize completeness and good fortune, with each ingredient carrying its own meaning—lotus seeds for fertility, jujubes for happiness, and longans for family unity.

Breakfast Traditions: Starting the Year Right

The first meal of the New Year is as significant as the reunion dinner. Yuánxiāo (glutinous rice balls) are a breakfast staple, especially in northern Beijing. These chewy orbs, filled with sesame paste or crushed peanuts, are boiled and served in a sweet broth. Their round shape mirrors the full moon, symbolizing reunion and wholeness.

For a savory breakfast, jīdàn guǒzi (egg pancakes) are a popular choice. Made with a thin crepe filled with egg, scallions, and a savory sauce, these pancakes are both comforting and energizing—a fitting start to a day filled with visits to relatives and temple fairs.

Modern Twists on Timeless Traditions

While Beijing’s Spring Festival cuisine remains deeply rooted in tradition, modernity has introduced subtle shifts. Health-conscious households now incorporate steamed or baked versions of traditional dishes, such as dumplings filled with lean meat and vegetables. Fusion recipes, like dumplings stuffed with cheese or truffle oil, cater to younger generations with adventurous palates.

Vegetarian and vegan options are also gaining traction, with mock meats and plant-based fillings replacing pork or beef. These adaptations reflect broader societal changes while preserving the holiday’s spirit of togetherness.

Rituals and Superstitions: Eating with Intent

Beyond the dishes themselves, Beijing’s Spring Festival meals are steeped in rituals. It is considered bad luck to use knives or sharp objects on New Year’s Day, as they symbolize severing ties. Instead, foods are pre-cut or served whole. Similarly, serving an odd number of dishes is avoided, as even numbers represent balance and harmony.

The act of sharing food is equally symbolic. Elders often pass dishes to younger family members, a gesture that reinforces filial piety. Children are encouraged to eat heartily, as full bowls are believed to bring good health and academic success.

Conclusion: A Feast That Transcends Time

Beijing’s Spring Festival cuisine is a living testament to the city’s enduring cultural identity. Each dish—from the humble dumpling to the elaborate eight-treasure pudding—tells a story of resilience, hope, and familial love. In an era of rapid change, these traditions remain a steadfast anchor, reminding Beijingers of their shared heritage. As the city evolves, so too will its culinary landscape, but the heart of the Spring Festival feast—a celebration of life’s simplest and most profound joys—will endure.

In the end, the act of eating during this sacred season is not merely about sustenance. It is a dialogue with the past, a celebration of the present, and a hopeful gesture toward the future. And in Beijing, that dialogue is always served piping hot, seasoned with love, and shared around a table brimming with tradition.

0 comments