Table of content

Pineapples, with their spiky exteriors and vibrant golden flesh, are a tropical delight enjoyed worldwide. Yet, despite their popularity, many people remain unaware of the botanical intricacies of this fruit. A common question lingers: When we eat a pineapple, which part of the plant are we consuming? This article delves into the anatomy of a pineapple, exploring its structure, edible components, and the science behind its culinary appeal. By the end, you’ll not only know which part to savor but also gain a deeper appreciation for this fascinating fruit.

The Botanical Structure of a Pineapple

To understand what part of the pineapple we eat, we must first dissect its botanical makeup. A pineapple (Ananas comosus) is not a single fruit in the conventional sense but a multiple fruit, also known as a sorosis. This means it forms from the fusion of hundreds of individual flowers (florets) that merge into one fleshy mass. The result is a complex structure composed of several distinct parts:

- The Crown (Leaves): The spiky, green tuft at the top of the pineapple is its crown. These leaves are modified stems and serve as the plant’s photosynthetic engines. While inedible raw, they can be propagated to grow new pineapple plants.

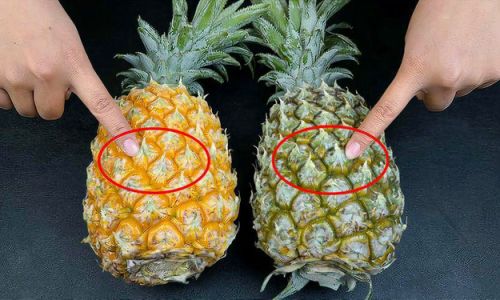

- The Peel (Rind): The tough, hexagonal-patterned exterior is the peel or rind. It protects the inner flesh from pests and environmental stressors. Though not typically eaten raw, it contains bromelain—an enzyme with culinary and medicinal uses.

- The Flesh (Edible Portion): Beneath the peel lies the juicy, aromatic flesh. This is the part most people recognize as the “pineapple.” It’s composed of fused berries (called eyes) that develop from the ovaries of the merged flowers.

- The Core: A fibrous, cylindrical core runs through the center of the pineapple. Many assume it’s inedible, but it’s actually a nutrient-rich part of the fruit, albeit tougher than the surrounding flesh.

The Edible Parts: Flesh, Core, and Beyond

The Flesh: Nature’s Candy

The flesh is the star of the pineapple. Sweet, tangy, and bursting with juice, it’s the primary reason this fruit is cultivated globally. The flesh’s texture and flavor vary slightly depending on ripeness and variety. For example, the “Smooth Cayenne” variety, common in canned pineapples, is fibrous, while the “Red Spanish” type has a crisper texture.

Nutritionally, the flesh is a powerhouse. It’s rich in:

- Vitamin C: Boosts immunity and skin health.

- Manganese: Supports bone health and metabolism.

- Bromelain: A protein-digesting enzyme that aids digestion and reduces inflammation.

The Core: A Hidden Gem

The core, often discarded, deserves a second look. While tougher and less sweet than the flesh, it’s edible and packed with bromelain. Cooking or blending the core softens its texture, making it palatable. Some health-conscious individuals even juice the core for its enzymatic benefits.

The Peel: Not Just Waste

Though inedible raw, the peel has culinary uses. Boiling it in water creates a tangy broth, while drying and grinding it yields a pineapple-flavored powder. The peel’s bromelain content also makes it useful for tenderizing meat—a practice in many traditional cuisines.

Historical and Cultural Context

Pineapples originated in South America, with the indigenous peoples of Paraguay and Brazil domesticating them over 6,000 years ago. European explorers, including Christopher Columbus, encountered pineapples during their voyages and introduced them to the Old World. By the 17th century, pineapples became a symbol of luxury in Europe, with colonies like Hawaii later emerging as major producers.

Culturally, pineapples hold significance beyond the kitchen:

- In Hawaii, they represent hospitality and are carved into doorways to welcome guests.

- In colonial America, renting a pineapple for a party was a status symbol.

- Today, pineapples adorn everything from art to fashion, symbolizing warmth and tropical escapism.

Culinary Versatility: From Breakfast to Dessert

The pineapple’s edible parts—flesh, core, and even peel—lend themselves to countless dishes:

Fresh Consumption

The simplest way to enjoy a pineapple is raw. Cut off the peel, remove the eyes, and slice the flesh into rings or cubes. The core can be blended into smoothies or eaten raw for a fibrous chew.

Cooked Applications

- Grilling: Caramelizing pineapple slices on the grill enhances their natural sweetness.

- Baking: Pineapple upside-down cake, a classic dessert, uses the fruit’s acidity to balance rich batter.

- Savory Dishes: Hawaiian pizza, a controversial but beloved dish, pairs pineapple with ham and cheese.

Preserved and Processed

Canned pineapple, a pantry staple, is made from peeled and cored flesh. The core is often removed during processing, but some brands now market “cored” varieties to reduce waste.

Non-Culinary Uses

- Bromelain: Extracted from the core and stem, this enzyme is used in meat tenderizers, digestive supplements, and anti-inflammatory creams.

- Alcohol: In the Philippines, barako pineapple wine is fermented from the fruit’s juice.

The Science of Pineapple Digestion

Pineapple’s unique enzyme, bromelain, plays a dual role in culinary and biological contexts. In the kitchen, it breaks down proteins, making meat tender. In the human body, bromelain aids digestion by breaking down food proteins and reducing inflammation. However, consuming large quantities of raw pineapple can cause tongue irritation due to bromelain’s proteolytic activity—a temporary side effect that subsides as the enzyme is deactivated by stomach acid.

Myths and Misconceptions

-

“The core is poisonous.”

False. The core is safe to eat, though tougher than the flesh. Cooking or blending softens it. -

“The peel is inedible.”

Partially true. While the peel isn’t typically eaten raw, it’s not toxic. It can be used in broths or extracts. -

“Pineapples grow on trees.”

False. Pineapples grow on low-lying plants close to the ground. Each plant produces one fruit per season.

Sustainability and Ethical Considerations

Pineapple cultivation faces environmental challenges. The fruit requires significant water and fertilizer, and monoculture farming in places like Costa Rica and the Philippines has led to deforestation. However, sustainable practices, such as drip irrigation and shade farming, are gaining traction. Consumers can support ethical production by choosing fair-trade or organic pineapples.

Conclusion: Savoring the Pineapple’s Bounty

Next time you enjoy a slice of pineapple, remember: you’re eating the fused berries of a multiple fruit, with the core offering hidden nutritional benefits. From its historical roots in South America to its modern-day culinary dominance, the pineapple remains a testament to nature’s ingenuity. Whether grilled, baked, or blended, this tropical treasure invites us to savor not just its flavor, but the story it carries from crown to core.

So, the next time someone asks, “What part of the pineapple do we eat?” you can confidently reply: “All of it—from the sweet flesh to the fibrous core, each bite is a gift from the plant’s intricate design.”

0 comments