Introduction

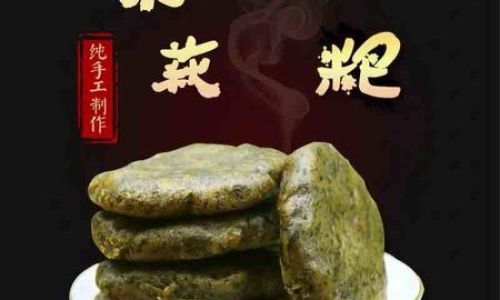

Anhui Province, nestled in eastern China, is renowned for its picturesque landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and distinctive cuisine. Among its culinary treasures is Shuiqiuba (水秋粑), a seasonal rice cake deeply rooted in autumn traditions. This humble yet flavorful dish embodies the region’s agricultural bounty and culinary craftsmanship, often prepared during harvest festivals or chilly autumn evenings. Made from glutinous rice flour and filled with aromatic ingredients, Shuiqiuba offers a chewy texture and a delicate balance of sweetness and earthiness. This article delves into the history, cultural significance, and meticulous process of crafting this beloved Anhui specialty, ensuring even novice cooks can recreate its magic.

The Cultural Tapestry of Shuiqiuba

Shuiqiuba’s origins trace back to Anhui’s rural communities, where autumn marked the conclusion of the harvest season. Farmers, exhausted from months of labor, would gather to celebrate with communal feasts featuring locally grown ingredients. Rice, a staple crop, formed the backbone of these celebrations, and creative preparations like Shuiqiuba emerged as both a nourishing meal and a symbolic offering to nature’s abundance.

The dish’s name, Shuiqiuba, literally translates to “water autumn cake,” reflecting its seasonal association with autumn and the liquid-rich preparation method. Unlike steamed or fried cakes, Shuiqiuba’s dough is kneaded with boiling water, creating a uniquely soft and pliable texture. This technique also symbolizes the “water of life” that sustains crops, linking the dish to themes of gratitude and renewal.

Today, Shuiqiuba remains a cherished part of Anhui’s culinary identity, often served during festivals like the Mid-Autumn Festival or as a comforting snack on crisp autumn days. Its preparation is also a communal activity, with families and neighbors coming together to roll, fill, and steam the cakes, fostering connections that transcend generations.

Ingredients: The Essence of Anhui’s Bounty

Crafting authentic Shuiqiuba requires a harmonious blend of simple, high-quality ingredients. While variations exist, the classic recipe emphasizes locally sourced components that highlight Anhui’s agricultural diversity.

For the Dough:

- Glutinous Rice Flour (200g): The star ingredient, providing the cake’s signature chewiness. Opt for finely milled flour for a smoother texture.

- Wheat Starch (50g): Added to enhance elasticity and prevent stickiness.

- Boiling Water (150ml): Critical for activating the glutinous rice flour’s stickiness.

- Salt (1/4 tsp): A subtle seasoning to balance sweetness.

- Sesame Oil (1 tbsp): Optional, but adds a nutty aroma.

For the Filling (Sweet Variation):

- Black Sesame Paste (100g): Toasted and ground sesame seeds mixed with sugar.

- Sugar (50g): Adjust to taste; brown sugar offers a caramel-like depth.

- Osmanthus Flowers (1 tbsp, dried): A fragrant botanical common in Anhui, imparting a floral note.

- Pork Lard (20g): Traditional for richness, though coconut oil can substitute for vegans.

For the Filling (Savory Variation):

- Minced Pork (150g): Preferably shoulder meat for juiciness.

- Shiitake Mushrooms (50g, dried): Rehydrated and finely chopped.

- Bamboo Shoots (100g): Blanched and diced for crunch.

- Soy Sauce (1 tbsp): Use dark soy for color.

- Ginger (1 tsp, grated): Fresh ginger enhances savory notes.

- Sesame Oil (1 tsp): For fragrance.

Equipment:

- Steamer basket

- Cheesecloth or parchment paper

- Mixing bowls

- Rolling pin

- Wooden spatula

The Art of Preparation: Step-by-Step

Dough Mastery

The dough’s success hinges on precise water temperature and kneading technique. Begin by sifting the glutinous rice flour and wheat starch into a heatproof bowl to aerate the mixture. Gradually pour in the boiling water while stirring vigorously with a wooden spatula. The heat partially cooks the flour, creating a sticky, elastic mass. Once cool enough to handle, knead the dough for 8–10 minutes until smooth and springy. Cover with a damp cloth to prevent drying.

Pro Tip: If the dough feels too stiff, moisten your hands with cold water and continue kneading. Overworking can make it gummy, so stop once it bounces back when pressed.

Filling Alchemy

Sweet Filling:

Toast black sesame seeds in a dry pan until fragrant, then grind with a mortar and pestle. Mix with sugar, osmanthus flowers, and melted lard until a cohesive paste forms. Chill briefly to firm up.

Savory Filling:

Sauté minced pork until browned, then add shiitake mushrooms and bamboo shoots. Stir in soy sauce, ginger, and sesame oil. Cook until the liquid evaporates, then cool completely.

Shaping the Cakes

Divide the dough into 30g portions (golf ball-sized). Flatten each into a 4-inch circle using a rolling pin, ensuring the edges are thinner than the center. Spoon 15g of filling into the center, then pinch the dough edges together to seal. Gently flatten the sealed cake into a thick disc.

Traditional Touch: Anhui cooks often imprint a decorative pattern using a bamboo skewer or mold, though this is optional.

Steaming to Perfection

Line the steamer basket with cheesecloth or parchment to prevent sticking. Arrange the cakes 1 inch apart and steam over medium heat for 12–15 minutes. Avoid opening the lid mid-steam to prevent temperature drops. The cakes are ready when they puff slightly and turn translucent.

Serving Suggestions:

Brush with honey or serve with a side of ginger syrup for sweet Shuiqiuba. For savory versions, pair with chili oil or black vinegar.

Cultural Nuances and Regional Variations

While the core recipe remains consistent, Anhui’s diverse regions infuse local twists into Shuiqiuba. In the mountainous Huangshan area, cooks might add wild mushrooms or chestnut flour to the dough. Along the Yangtze River, where fishing is prevalent, shrimp or crab roe fillings occasionally appear. Urban chefs now experiment with modern fillings like matcha or red bean paste, though purists advocate for traditional preparations.

Preservation and Modern Adaptations

Shuiqiuba is best enjoyed fresh, but leftovers can be refrigerated for 2–3 days. Reheat by steaming or pan-frying with a touch of oil for crispy edges. Gluten-free variations use rice flour and tapioca starch, while vegan versions replace lard with coconut oil.

Conclusion

Shuiqiuba is more than a dish—it’s a testament to Anhui’s agricultural soul and communal spirit. From the meticulous kneading of dough to the steamy aroma filling kitchens, each step honors traditions passed through centuries. Whether savored during a festival or a quiet autumn evening, this water rice cake bridges past and present, offering a taste of Anhui’s heart and history. As you embark on your Shuiqiuba journey, remember that patience and respect for ingredients are the true seasonings of this culinary masterpiece.

0 comments